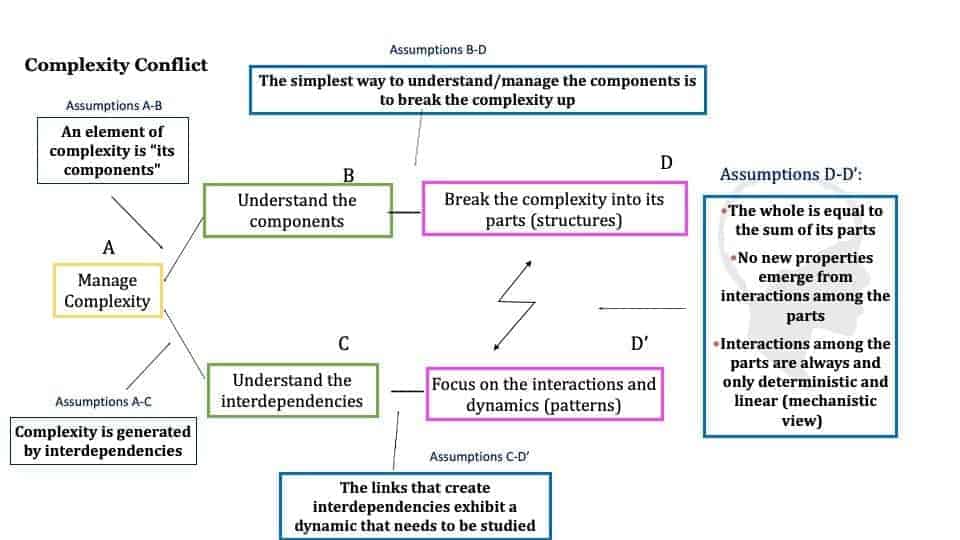

‘Complexity’, the science that studies what happens when things start interacting, has been largely ignored when it comes to designing and managing (not to mention measuring) organizations. Using a systemic thinking process from the Theory of Constraints (TOC), we can summarize it as follows:

When we map out a conflict using the conflict cloud, we can then read it from left to right as follows: If our goal is to manage complexity, and an element of complexity is its components, then we need to understand the components, and if the simplest way to understand/manage the components is to break the complexity up, then we want to break the complexity into its parts (focus on the elements that make up the structures).

On the other hand, if our goal is to manage complexity, and complexity is generated by interdependencies, then we need to understand the interdependencies, and if the links that create the interdependencies exhibit a dynamic that needs to be studied, then we want to focus on the interdependencies and dynamics (focus on the patterns).

We are in the conflict between D and D’ because we make the assumptions that: the whole is equal to the sum of its parts; no new properties emerge from interactions among the parts; interactions among the parts are always and only deterministic and linear (mechanistic view).

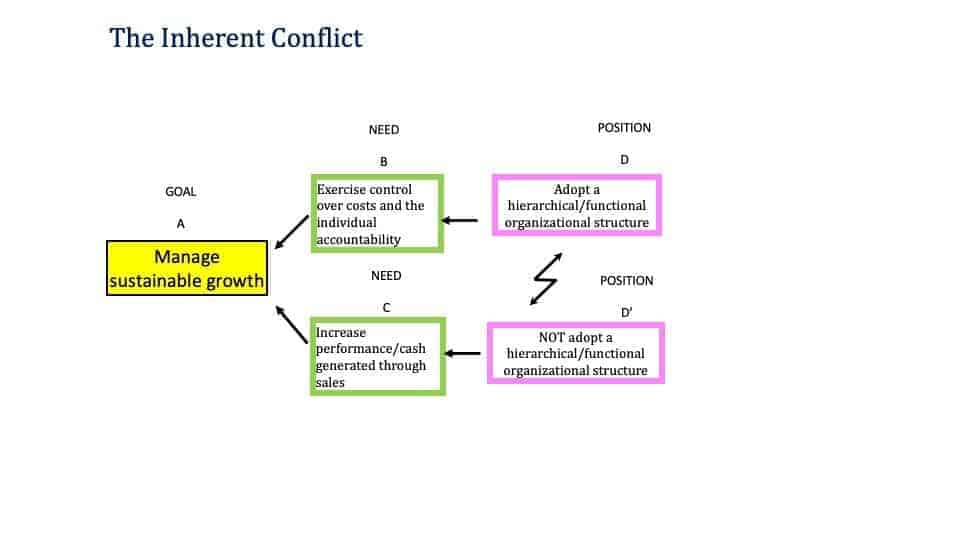

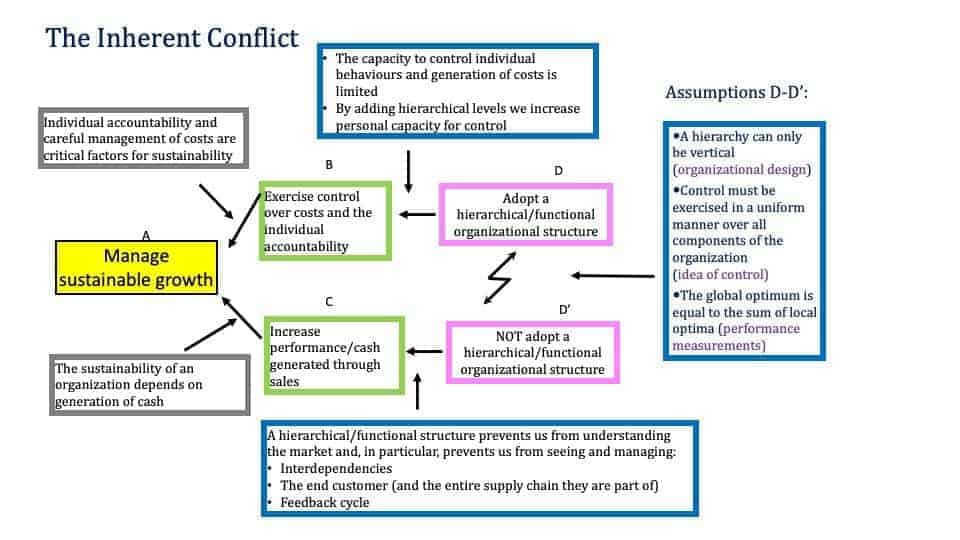

Indeed, this is a completely generic verbalization, but when applied to organizations it takes the following shape:

In other words: even in the face of a blatant inadequacy to cope with reality, conventional hierarchies (functional silos) still often prevail, plunging organizations into this conflict.

We first presented this paradigmatic conflict in our 2010 book ‘Sechel: Logic, Language and Tools to Manage Any Organization as a Network’ and later in our 2016 book ‘Quality, Involvement, Flow: The Systemic Organization‘ published by CRC Press.

In the aftermath of the 2007 crisis, following a very hard professional defeat, my team at Intelligent Management and I started to ask ourselves how it is possible, operationally not just conceptually, to come out of this conflict. We set out to find a generally applicable solution, something that would help us overcome this dichotomy. The starting point was The Decalogue, developed 10 years earlier with Oded Cohen and first published in 1999 by Dr. Goldratt’s publisher North River Press as ‘Deming and Goldratt: The Decalogue‘.

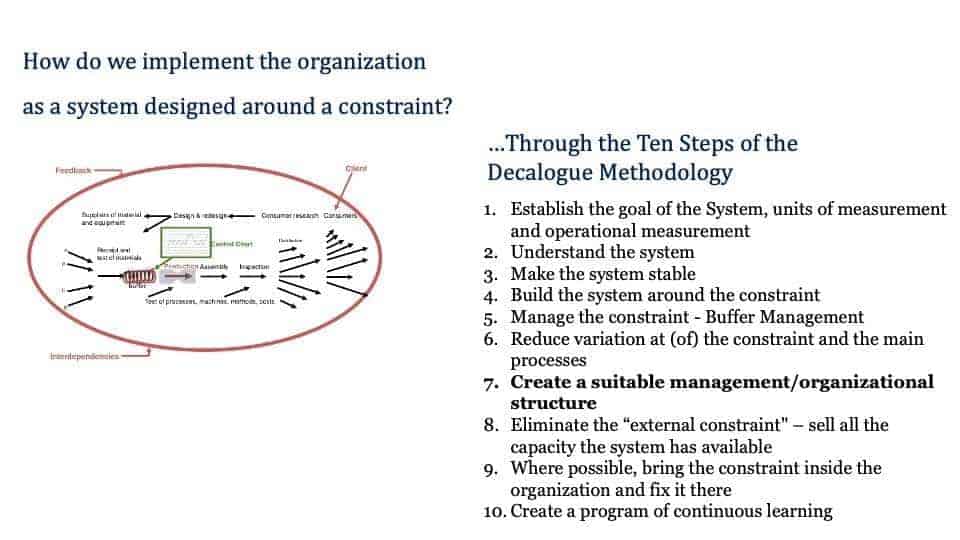

The Ten Steps of the Decalogue are:

- Establish the goal of the system, units of measurement, and operational measurement.

- Understand the system (map the interdependencies).

- Make the system stable (manage variation so that processes are statistically predictable).

- Build the system around the constraint – a strategically chosen leverage point.

- Manage the constraint (buffer management).

- Reduce variation at (of) the constraint and the main processes.

- Create a suitable management/organizational structure.

- Eliminate the ‘external constraint’ – sell all the capacity the system has available.

- Where possible, bring the constraint inside the organization and fix it there.

- Create a program of continuous learning.

In essence, what we wrote is that there is an algorithm, a protocol, to ensure long-term sustainable growth for any organization and a coherent systemic design that this protocol engenders.

What we came to realize is that, if this is the inherent conflict of organizations and these are the key assumptions (mental models) between D and D’ that make the conflict persist…

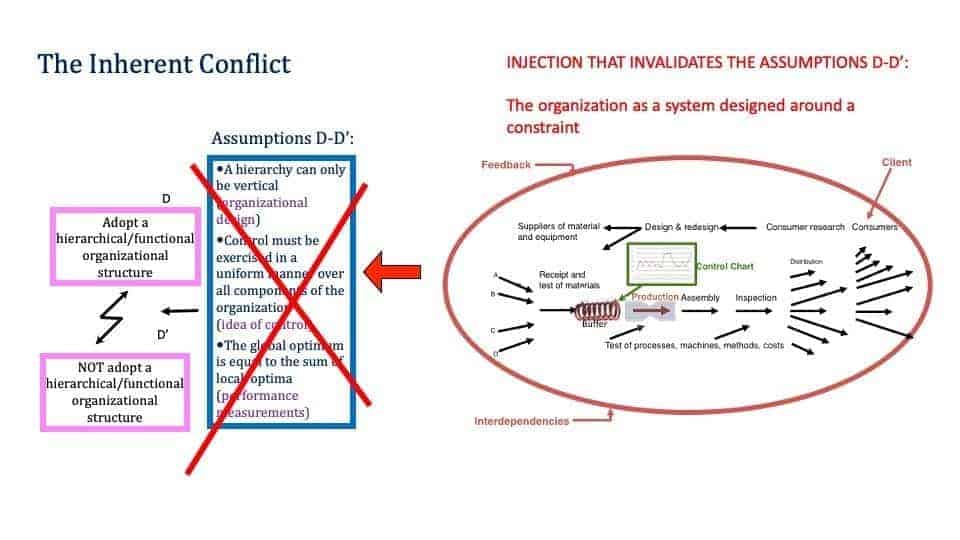

…then we need to find an ‘injection’ – a systemic solution that invalidates the assumptions between D and D’ while protecting the legitimate needs in B and C of the conflict cloud.

The solution we developed to overcome the inherent conflict is the organization as a system designed around a constraint.

The missing piece

Yes, ‘The Organization seen as a system’, constrained in one strategically chosen point, protected by a buffer whose oscillation is managed according to the principles set forth by Walter Shewhart (and magnified by the work of Dr. Deming), is indeed the injection (solution) to the conflict and a solution for sustainable growth, allowing an organization to scale without creating silos. But how, exactly, can we bring it to fruition with the aid of The Decalogue? How do we put it into action?

In 1999, we still did not have a sufficiently generic and comprehensive answer to how to put a systemic organization design into action. And neither did academics, pundits and advocates for many sigma statistical hallucinations and lean Japanese fantasies, who fared conceptually way worse than we did in trying to provide a workable solution. (By the way, ‘Deming and Goldratt: The Decalogue’ meanwhile had been published in Japan – although, I am afraid, probably something got lost in translation).

That answer came later; it had been in full display for years, but nobody saw it. My team and I started from the most fundamental question: What do organizations do?

If you look at what any person does at work, you can safely say that there are only two types of activities: recurring and one-off.

The former, if executed with some level of statistical predictability (good morning quality!) allows the flourishing of the latter. Without statistically stable recurring (and somewhat repetitive) processes, organizations have no sustainable life. They represent, metaphorically, the roots that allow the tree to grow. When we map these processes, weed out inconsistencies, educate all the relevant people to their ways and manage their upkeep, we have a solid starting point to build upon.

Build what?

What keeps organizations in business? Heeding their customers and providing them with what they need. It is important to understand that the transformation of an expressed or unexpressed customer need into a saleable product/service is a project; it is the coordination of a set of (hopefully) well designed processes (tasks) aimed at delivering a chosen goal within an agreed upon timeframe, budget and specifications.

Management is the social science that allows organizations to transform (market) needs into (saleable) products and the vehicles for doing so are the projects. Accordingly, managing projects is what managers do.

Unfortunately, the current reality in organizations of all stripes is vastly different. The inherent conflict created by the hierarchical/functional organization design is still for the most part unaddressed and the global optimum (what investors and stakeholders at large want and need) is invariably sacrificed on the shrine of some local, cost-saving organizational efficiency. All this impedes growth that is sustainable over time. In Part 3 of this series, we will look at how to scale a business sustainably.

This is the second article in a series! If you would like to read the next one, click here. If you would like to read the first one, click here.

![business management rethink complexity [shutterstock: 1158637870, fran_kie]](https://e3zine.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/business-management-rethink-complexity-shutterstock_1158637870.jpg)

Add Comment