It’s not enough to have interesting ideas or suggestions. It requires a methodology and tools, and you need to know what you are doing and why (i.e. have an epistemological framework). In this series, we present a completely new way of looking at an existing method for working with projects as the key to transforming organizations, away from fragmentation and silos towards working smoothly and effectively as a synchronized whole, no matter how decentralized the company may be. This has been the core of our work at Intelligent Management for the last decade.

In 1997, I was among the few to receive from Larry Gadd, Dr. Goldratt’s Publisher at North River Press, the galley of ‘Critical Chain’. At the time, I had no idea how much it would have changed the development of my professional life (and, somewhat, impact my personal one).

It is very hard to overestimate its contribution to management. Simply put, ‘Critical Chain’ lays the foundation for a complete rethink of the role of management (and business school curricula) as well as ushering in a new paradigm in the meaningful deployment of human resources.

For us at Intelligent Management, Critical Chain has been a constant source of inspiration (and a prompt) to take its boundless implications to a new level. The work we have done in the last 10 to 12 years builds on my first book, ‘Deming and Goldratt: The Decalogue’ co-written with Goldratt’s lifetime partner, Oded Cohen. (It was the first book published by Goldratt’s publisher about the Theory of Constraints (TOC) that was not written by Goldratt himself).

This work has been a constant feedback between theoretical development and on-the-field validation; it has been elucidated in several books (‘Sechel: Logic, Language and Tools to Manage Any Organization as a Network’, 2010; ‘Quality, Involvement, Flow: The Systemic Organization’, 2016, CRC Press; and ‘Moving the Chains – An Operational Solution for Embracing Complexity in the Digital Age’, 2019, Business Expert Press.) We have also written hundreds of blog posts, given webinars, and more.

The essence of the work is this: A new, genuinely systemic organizational design emerges from the understanding of Critical Chain Project Management (CCPM), one that allows companies to overcome the prevailing hierarchical, silo-based organization. We called it ‘The Network of Projects’.

True to the spirit of continuous innovation and development engendered by Dr. Deming and Dr. Goldratt’s message, at Intelligent Management we have taken another step in the direction of making their knowledge more available and practically implemented.

In 1997, Dr. Goldratt published ‘Critical Chain’, throwing down a gauntlet to the sleepy world of MBA programs, guilty of not being innovative enough in equipping students with truly useful (and usable) knowledge. The arena he chose this time was ‘New Product Development’ (and the project management needed to bring the product to life).

Just like he had done with ‘The Goal’ (production and logistics) and ‘It’s not luck’ (marketing, sales and distribution), Dr. Goldratt examines the current reality of project management, surfaces its self-limiting beliefs (assumptions) and develops a breakthrough solution, Critical Chain Project Management (CCPM).

At the core of ‘Critical Chain’, just like Drum Buffer Rope in ‘The Goal’, there is the common sense, yet revolutionary, concept of ‘finite capacity scheduling’: you cannot have the same person work on two different tasks at the same time. Scheduling must be realistic.

Critical Chain (CC) was immediately hailed by the Theory of Constraints (TOC) community as a game-changing innovation and widely regarded as a genuine breakthrough by project managers around the globe; however, it took several years for CC to become adopted on a significant scale. Still today, only a tiny fraction of PM professionals have a solid grasp of it.

Why is that? In my opinion, two main factors have contributed to the relatively limited dissemination of CCPM.

- It has always been presented as a project management technique and its target has been PM professionals, arguably a category with limited span of authority to influence organizational changes.

- Just like quality management, project management has been slotted into a ‘silo’ (the PMO office…) and wrapped up in diplomas and certifications organized and administered by PMI (Project Management Institute), the most staunch denier of finite capacity scheduling (but, hopefully, persuaded that the earth is not flat and Neil Armstrong did go to the moon). Still today, PMI does not make CC part of its curriculum.

In other words: the transformational message of ‘Critical Chain’ and its underpinning revolutionary approach to the management of people has been largely debased by misleading communication and commercial interests.

A new perspective for business management

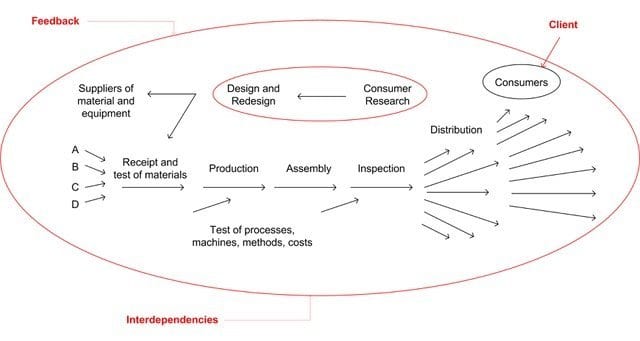

By the beginning of the new millennium, every single element of knowledge needed for management to evolve into a legitimate social science (not unlike Economics, Sociology, etc.) were in place, published and available internationally. Both Deming and Goldratt had laid out theory, principles and methods to guide management from the quicksand of empiricism (“Let’s try something and see what happens” – I don’t really know what I am doing) to the safe shore of epistemology (“If I do this, I expect that to happen” – I have a theory and I seek its realm of validity through planned experiments). Foundational to this new perspective is the understanding that an organization is a system, as Deming began explaining as far back as the 1950s. To paraphrase Deming: An organization is a system; a network of interdependent people and resources working in processes and projects to achieve a common goal.

Deming depicted this with his diagram ‘Production Viewed as a System’ that we have represented below.

Moreover, some management thinkers in universities around the globe were beginning to point out the fallacy of prevailing management methods, almost invariably based on cost-accounting type considerations. The overarching theme of ‘complexity‘ was beginning to raise its head and, starting from the 9/11 tragedy through to the 2007 financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic, the world has increasingly had to come to terms with it. In Part 2 of this series, we will look at what complexity means for organizations and the core problem preventing companies from achieving sustainable growth.

This is the first article in a series! If you would like to read the next one, click here.

![business management intelligent management [shutterstock: 243215554, jannoon028]](https://e3zine.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/business-management-intelligent-management-shutterstock_243215554.jpg)

Add Comment